Share this Story

A Bridge too Far:

The Death March – Endurance in the Face of Collapse

For the men of the 3rd Battalion, survival didn’t end with the battle at Arnhem. Nor did it end behind the wire at Stalag XI-B. When the bitter winter of 1945 descended, and the Allied lines pushed deep into German territory, what remained of their suffering took to the road. It wasn’t a journey. It wasn’t a transfer. It was a slow, staggering exodus into the unknown—one that would later be known as one of the most traumatic final chapters of the war: The Death Marches.

These weren’t organised troop movements—they were chaotic evacuations driven by fear, desperation, and Nazi denial. Thousands of prisoners, already broken in body and spirit, were ordered to walk for days—sometimes weeks—with little food, no medical care, and no destination. It was less a relocation and more a mobile prison, stretched out across frozen roads and fields, shadowed by death every step of the way. For many, it would become the final battlefield—fought not with bullets or bombs, but with every exhausted footstep and every ounce of will left in their battered frames.

A Final Cruelty: Orders to Evacuate

In early 1945, the German High Command gave orders to evacuate POW camps that lay in the path of advancing Allied troops. The goal was to prevent prisoners from being liberated and potentially rejoining the fight, or worse—becoming witnesses to the atrocities committed in the east. Some Nazi leaders still clung to the fantasy that holding Allied POWs could give them leverage at the negotiation table.

At Stalag XI-B, a camp already at breaking point from overcrowding, disease, and starvation, the command came down: the prisoners were to march. No destination was given. No preparations made. Men were simply told to gather what little they had and move out. Some were barefoot. Many wore lice-ridden uniforms stiff with sweat and mud. Most were already dangerously malnourished.

And so they walked—thousands of them—through snow, through frozen fields, through the collapsing remnants of the Third Reich.

“We passed the partially snow-covered bodies of hundreds of dead Jews, some of whom had died from cold or their exertions, while others had been shot.”

Arthur Dodd – British Army Driver and Auschwitz POW

“We were forced to march, some of us in terrible pain. The Germans showed no mercy. Every step was agony, but we had no choice but to keep moving.”

Sgt. Pilot James “Dixie” Deans – RAF POW and Camp Leader at Stalag 357

“I will give you a pass and a guard. Go and find the British.”

Oberst Hermann Ostmann – German Commandant at Stalag 357

Firsthand quotes from German soldiers directly referencing the Death Marches from Stalag XI-B are rare. Most German personnel didn’t leave personal accounts, and many records were destroyed or never created. However, we know from the actions of commandants like Oberst Hermann Ostmann—who allowed POW leaders to negotiate surrender—that some moments of reluctant humanity did exist amidst the brutality.

The March Begins: Cold, Hunger, and Uncertainty

The cold was immediate. The German winter in February 1945 was vicious—temperatures plunged well below freezing at night, and snow fell steadily on the bleak, grey landscapes of Lower Saxony. The marchers were given no maps, no explanation, and no clear end. It was rumoured they were heading south to Stalag XIII-C, but few believed they’d survive long enough to see it.

It tells us of men who carried their suffering with dignity, not for medals or headlines, but because there was no other way to keep moving forward. It tells us of comradeship stronger than death, forged in frozen fields, when a dying man would give his only blanket to someone worse off than himself. It tells us of the shuffling rhythm of boots on snow, the wheezing breath of men too tired to cry, and the numb hope that maybe—just maybe—this would be the last road.

Marecheal never walked in remembrance parades. He never stood for interviews. He didn’t keep medals on the mantelpiece or regale anyone with stories of ‘what it was like.’ What it was like stayed with him.

But in that unspoken grief, in that haunted quiet, is the voice of every man who walked that road and couldn’t bear to relive it. And through the testimonies of others—those who did speak, those who could—we begin to understand what Marecheal could not bring himself to say.

“It was a march to nowhere. We had no idea where we were going or when it would end. All we knew was that death was everywhere—at the side of the road, in the frozen fields, in the air.”

Pvt. Tom Baker, 3rd Btn Paras.

Some men marched with the memory of Arnhem still raw — the sound of mortars, the screams of wounded comrades, the faces of those left behind in basements turned to rubble. Others had barely survived Stalag XI-B, their bodies already weakened by dysentery, frostbite, or starvation. Some coughed blood into the snow as they walked. Some limped with the help of makeshift crutches. For men like Marecheal, there was no triumph, no talk of duty or medals. There was only that grim, unspoken resolve: one foot in front of the other.

He never described what he saw. Not once. Not in passing, not in old age, not when asked. His silence was complete—and telling. But others did speak, and from their recollections, we know what that silence was built upon: the sight of men collapsing in ditches, never to rise again; the stiffening of limbs in the cold, the blank stares of those who’d stopped believing rescue would come. One survivor described waking to find the man beside him dead, frozen stiff in the night. Another remembered passing bodies piled at the roadside, covered hastily with twigs and snow—no names, no prayers, just a place to leave them.

These were not marches of discipline or order. They were slow-moving human graveyards. And Marecheal, like thousands of others, walked every step in silence—with the weight of Arnhem behind him and the threat of oblivion ahead.

Human Endurance at Its Limit

The march went on for days. Some men walked over 200 kilometres. They slept in barns, under carts, in snowbanks. There were no fires, no medical care, and barely any food. Red Cross parcels, where they existed, were often pillaged by guards. The men chewed on raw turnips, ate bark, or drank from ditches if they were lucky enough to find water.

Their feet split and bled inside rotting boots. Their limbs turned blue from exposure. Some lost toes to frostbite. And yet they kept going—because stopping meant death.

Their feet split and bled inside rotting boots. Their limbs turned blue from exposure. Some lost toes to frostbite. And yet they kept going—because stopping meant death.

One British corporal, unnamed in records, reportedly told a fellow marcher:

“I’ve come too bloody far to die in a ditch.”

Every few miles, a man would drop. A few would try to help him. Others, too weak to lift their heads, walked past with hollow eyes. They had nothing left to give.

RSM John Lord, who had kept discipline alive inside Stalag XI-B, said of the march, “The only thing we had was each other. I told the lads, if you can’t march for yourself—march for the man next to you.”

The Tragedy at Gresse

By late April 1945, the column of prisoners reached Gresse, a small village east of the River Elbe. They were barely more than shadows of soldiers—emaciated, frostbitten, some delirious from hunger and fever. They had walked for days, maybe weeks, through ice, snow, and frozen mud. Liberation was now so close they could feel it in the air. Allied artillery rumbled faintly on the horizon. Hope, fragile as it was, began to flicker.

On 19 April 1945, as the column of British and Commonwealth POWs trudged along a country road near Gresse, a formation of British Typhoon fighter-bombers appeared overhead. From the air, the line of movement—staggered columns, wagons, and German guards—looked like a retreating Wehrmacht convoy. There was no communication, no markings clear enough to distinguish friend from foe, and no time to correct the mistake.

The Typhoons opened fire! In an instant, the peaceful countryside erupted in gunfire and flames. Rockets and cannon fire ripped through the column, striking POWs and guards alike. Men who had survived Arnhem, Stalag XI-B, and the Death March now fell to friendly fire—cut down just days before the end of the war. Sixty prisoners were killed. Dozens more were wounded.

Those who could still move dove for cover—into hedgerows, roadside ditches, behind tree stumps. One survivor, unable to forget the horror, later described crawling over the bodies of his comrades to find shelter. The snow, trampled and muddied by weeks of marching, was now streaked red with blood. There was no warning. No second wave of relief. Just confusion, chaos, and silence once the aircraft were gone. Many of the survivors had to bury their friends that night in shallow graves along the road! A chaplain among the POWs reportedly read from memory the 23rd Psalm, his voice shaking with grief, “The Lord is my shepherd… Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death…”, They had survived the camps, the marches, the hunger, the disease—only to die beneath the guns of those who’d come to save them. As one survivor later said, “We were too tired to even be angry. We just stared at the sky and asked why.”

The men of the 3rd Battalion—and many other POWs in that column—would carry the memory of Gresse with them forever. It was a wound that never made the medals or memorials. But it was no less real. It was the final betrayal of a war they’d already given everything to survive.

Liberation, at Last

Just days later, on 2 May 1945, the battered remnants of the Death March crossed into Allied territory. The nightmare was over—but the trauma had only just begun.

Some men collapsed into the arms of medics. Others tried to salute and stand, as RSM Lord had taught them. “We were soldiers still,” he would later say. “Even in rags, even half-dead—we stood to attention. That’s how they found us.” They had survived. But at what cost? Sgt. “Dixie” Deans, who had helped negotiate their surrender, reflected:

“We were free, but we were hollow. What we’d lost, we couldn’t get back. But we were alive.”

Many of the liberated men had to be carried into the field hospitals that followed behind the Allied advance. Their legs had seized. Some were too malnourished to eat solid food. Their eyes, sunken and bloodshot, told stories their mouths never would. The doctors and nurses did their best—but even they admitted, privately, that nothing in their training had prepared them for this.

Nurse Jean MacFarlane, who arrived with the British medical teams, later recounted, “We were unprepared for what we found. The men were skeletal, their eyes hollow. We did what we could, but it never felt like enough.”

Some men recovered. They returned to families, to streets and shops that felt foreign now. But others didn’t make it home. Some died from complications days after liberation—from infections, untreated wounds, or simply from the strain of having held on too long. For men like Marecheal, the war never left. He walked free—but never spoke a word of what he saw, what he lived through, or who he lost. He returned with his silence, and that silence became part of the cost.

Marecheal and the March That Was Never Spoken Of

Marecheal made it home. He crossed that final threshold—back to familiar streets, back to the faces of family, back to a world that had no idea what he’d endured. But, like so many others, he never spoke a word about the Death March. Not about the snow that burned through his boots. Not about the men who collapsed beside him and never rose again. Not about the Typhoon attack, where freedom came dressed in fire from the sky. Not about the frostbite, the lice, the dysentery, the bitter taste of stale crusts shared between five. Not a word.

It tells us of men who carried their suffering with dignity, not for medals or headlines, but because there was no other way to keep moving forward. It tells us of comradeship stronger than death, forged in frozen fields, when a dying man would give his only blanket to someone worse off than himself. It tells us of the shuffling rhythm of boots on snow, the wheezing breath of men too tired to cry, and the numb hope that maybe—just maybe—this would be the last road.

Marecheal never walked in remembrance parades. He never stood for interviews. He didn’t keep medals on the mantelpiece or regale anyone with stories of ‘what it was like.’ What it was like stayed with him.

But in that unspoken grief, in that haunted quiet, is the voice of every man who walked that road and couldn’t bear to relive it. And through the testimonies of others—those who did speak, those who could—we begin to understand what Marecheal could not bring himself to say.

Last in the Series: After Arnhem – Memory, Silence, and the Stories We Carry

Share this Story

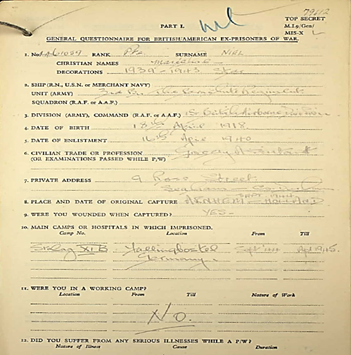

From Arnhem to Captivity – the journey of Marecheal Niel & the 3rd Btn Paras

Share this Story A Bridge too Far: From Arnhem to Captivity – the journey of Marecheal Niel and the 3rd Btn Paras The Battle of Arnhem, part of the audacious Operation Market Garden, was one of the most significant engagements…

The Stand at Arnhem – The 3rd Battalion’s Heroic Defense

Share this Story A Bridge too Far: The Stand at Arnhem – The 3rd Battalion’s Heroic Defense The story of Arnhem’s bridge is one of extraordinary courage, bitter determination, and unrelenting sacrifice. On September 17, 1944, Lt. Col. John Frost’s…

From Arnhem to Stalag XI-B – The Harrowing Journey of Capture, Captivity, and Liberation

Share this Story A Bridge too Far: From Arnhem to Stalag XI-B – The Harrowing Journey of Capture, Captivity, and Liberation The Battle of Arnhem had ended in chaos and defeat for the British 1st Airborne Division, but for the…